Strategy vs. Planning: Why “Strategic Planning” Is a Lie

Many organizations invest thousands of person-hours each year in strategic planning. Leadership teams run workshops, review market analysis, debate initiatives, analyze KPIs, and produce detailed plans.

Yet when asked a simple question — What is your strategy? — many leaders struggle to give a clear, consistent answer.

This is not a failure of effort. It is a failure of discernment.

What many organizations call strategy is actually planning — a confusion Roger Martin famously challenges in his Harvard Business Review article, “The Big Lie of Strategic Planning.”

The Uncomfortable Truth

Strategy and planning are not the same thing and confusing them creates false confidence and dilutes impact.

History has been consistent on this point. Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke in the 19th century observed that no plan of operations extends with certainty beyond first contact with the enemy. Decades later, Dwight D. Eisenhower captured the same idea differently: plans are worthless, but planning is everything.

These statements are not contradictory. They point to a shared truth:

Plans support action. They do not define intent.

That distinction is where many organizations lose clarity.

What Strategy Actually Is

At its core, strategy is an integrated set of choices designed to maximize the likelihood of success.

It answers three hard questions:

- Where will we play?

- How will we win?

- What are we explicitly choosing not to do?

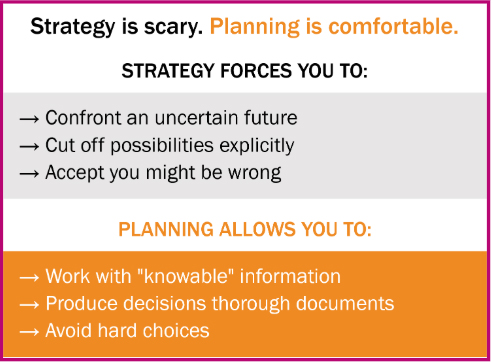

Strategy forces leaders to confront uncertainty, make tradeoffs, and accept the possibility of being wrong. That discomfort is not a flaw. It is a feature.

What Planning Is & Why It Feels Safer

Planning is about resource allocation. It translates choices into projects, timelines, budgets, and accountability.

Planning works with what feels knowable. It produces thorough documents and measurable outputs. It creates the appearance of control.

That is why organizations gravitate toward it.

Why “Strategic Planning” Persists

So why do leadership teams continue to invest heavily in strategic planning while avoiding real strategy?

Three forces are usually at play.

First, planning rarely challenges assumptions.

Its logic centers on affordability rather than customer value. It asks what can be funded, not what must be true to win.

Second, cost-based thinking feels more controllable than revenue bets.

Costs sit inside the organization’s control. Customers do not. Revenue planning often creates an illusion of certainty that strategy cannot provide.

Third, planning is career safe.

Few leaders are penalized for producing a comprehensive plan. Strategy requires bets, and bets carry visible risk.

The Hallmark of Real Strategy: Choice

One of the simplest tests of whether a document reflects real strategy is this:

Does It Clearly State What the Organization Will Not Do?

If it does not, the document is likely a plan dressed up in strategic language.

Roger Martin’s “Playing to Win” framework reinforces this point. Strategy requires clear answers to two fundamental questions:

- Where to play

- How to win

Capabilities, systems, and metrics follow from those choices. They do not substitute for them.

If a strategy requires a fifty-slide deck to explain, it is probably not clear enough.

Good Strategy Starts with Diagnosis

Richard Rumelt highlights another common failure. Organizations often skip diagnosis and move straight to goals.

Growth targets are not strategies. Objectives are not strategies. Initiatives are not strategies.

Good strategy begins by identifying the critical challenge, defining a guiding policy, and aligning a set of coherent actions around it. Without diagnosis, ambition replaces logic.

A Military Parallel Worth Remembering

To paraphrase Von Moltke, “No plan survives first contact with the enemy.” This is partly because, in combat, events start to move faster than the central authority can process information and make decisions. The generals in charge simply don’t have time to re-work the entire plan to accommodate these rapid developments.

Over the past century, the US military has developed the concept of “Commander’s Intent” to deal with this phenomenon. Military leaders are required to communicate their Commander’s Intent–: the purpose and desired end state of an operation–prior to its onset. This allows teams to adapt when plans break down, make decisions aligned with the mission, and exercise initiative within clear boundaries.

Strategy serves a similar purpose in business. As the pace of change continues to accelerate, traditional centralized corporate decision-making processes can start to break down. This makes having a clear, concise, and easily understandable strategy more important than ever.

The intent is the strategy.

The plan is how execution is expected to unfold.

When organizations blur the two, adaptability and agility disappears when they are needed most.

Shifting the Leadership Conversation

We’re not advocating that leaders abandon planning in favor of strategy. Planning and strategy are interdependent. To maximize the value of both important activities, it’s important to understand that effective planning can only happen once you’ve developed a strategy.

Leaders can start by changing the questions they ask:

- Instead of “What should we do?” ask “What are we betting on?”

- Instead of “Is this achievable?” ask “What would have to be true?”

- Instead of “What’s the plan?” ask “What is our theory of winning?”

These questions reflect the kind of strategic thinking Martin advocates — focused on choices, assumptions, and winning logic rather than static plans.

The Real Test

Pull out your current strategic plan and ask:

- Does it reflect clear choices about where we will and will not compete?

- Does it articulate a coherent theory of how we will win?

- Can frontline teams explain how their work connects to it?

If not, you may have a well-developed plan, but not a strategy.

The Takeaway

Strategy is not about certainty. It is about shortening the odds on the bets an organization chooses to make.

If your strategy feels entirely comfortable, it likely is not doing its job.

Planning still matters. But it belongs where it always has:

as the servant of strategy, not its substitute.

At Fahrenheit, we work with leadership teams to clarify strategy before committing to plans, helping organizations stay aligned and adaptable as conditions change.

By Peter Grimm, Practice Leader, Strategy & Operations